Last updated: 11-09-2022

In chapter two, Master Subodhi warns Sun Wukong that he must protect himself from “Three Calamities” (sanzai lihai, 三災利害) sent by heaven to punish him for achieving immortality and defying his fate (fig. 1). These punishments come every half millennia in the form of destructive elements:

Though your appearance will be preserved and your age lengthened, after five hundred years Heaven will send down the calamity of thunder [lei zai, 雷災] to strike you. Hence you must be intelligent and wise enough to avoid it ahead of time. If you can escape it, your age will indeed equal that of Heaven; if not, your life will thus be finished. After another five hundred years Heaven will send down the calamity of fire [huo zai, 火災] to burn you. The fire is neither natural nor common fire; its name is the Fire of Yin [yin huo, 陰火], and it arises from within the soles of your feet to reach even the cavity of your heart, reducing your entrails to ashes and your limbs to utter ruin. The arduous labor of a millennium will then have been made completely superfluous. After another five hundred years the calamity of wind [feng zai, 風災] will be sent to blow at you. It is not the wind from the north, south, east, or west; nor is it one of the winds of four seasons; nor is it the wind of flowers, willows, pines, and bamboos. It is called the Mighty Wind [bi feng, 贔風], and it enters from the top of the skull into the body, passes through the midriff, and penetrates the nine apertures. [1] The bones and the flesh will be dissolved and the body itself will disintegrate. You must therefore avoid all three calamities (Wu & Yu, 2012, pp. 121-122).

These calamities are important because Monkey subsequently learns the 72 transformations in order to escape punishment by hiding under any one of a myriad number of disguises. Therefore, exploring the origins of the three calamities has merit.

Fig. 1 – Master Subodhi tells Sun about the Three Calamities (larger version). Photomanipulation by the author.

I. Origins

The novel likely borrows from a Buddhist cosmological concept called the “Three Calamities” (sanzai, 三災). We first need some background before continuing. Buddhism recognizes a measurement of time called a Kalpa (jie, 劫), which can be many millions or even billions of years long depending on the tradition. Said traditions recognize between four and eighty kalpas (Buswell & Lopez, 2014, p. 409). The total of these respective ranges make up a Mahakalpa (dajie, 大劫), which is divided into four periods of nothingness, creation, subsistence, and finally destruction, each period being between one and twenty kalpas long (Buswell & Lopez, 2014, p. 496). The Three Calamities are responsible for the destruction of each Mahakalpa.

Kloetzli (1983) describes the cyclical destruction of each Mahakalpa by an element:

The destructions are of three kinds: those by fire, those by water and those by wind. […] The destructions succeed one another in the following sequence: seven by fire followed by a destruction by water. This cycle of eight destructions is repeated a total of seven times. This is then followed by seven more destructions by fire, followed by a final by wind. Thus there are 7 x 8 or 56 destructions by fire; 7 by water and a final 64th by wind [fig. 2] (p. 75).

Therefore, the Three Calamities from Journey to the West follow a similar cycle of destructive elements appearing at set time intervals: lightning, fire, and wind every 500 years in place of fire, water, and wind at the end of every Mahakalpa. And instead of destroying the universe, the elements are sent to kill those who have achieved immortality.

Fig. 2 – A chart mapping the cyclical destructions by fire, water, and wind. A larger version is available on the CBETA page.

The earliest mention of Buddhism’s Three Calamities in Chinese writing that I know of appears in scroll one of the Pearl Forest of the Dharma Garden (Fayuan zhulin, 法苑珠林), a Chinese Buddhist encyclopedia published in 688. So there was plenty of time between this work and the publishing of Journey to the West in 1592.

II. Influence on Xianxia literature

I was interested to learn that Monkey’s calamities made their way into modern Xianxia (仙侠, “Immortal hero”) literature. For example, the author of the Immortal Mountain wordpress writes:

Heavenly Tribulation (天劫 tiānjié) (重劫 zhòngjié) – in some novels, a trial encountered by cultivators at key points in their cultivation, which they must resist and ultimately transcend. Because immortal cultivation (generally) goes against the Will of Heaven, the Heavens will send down tribulations to oppress high-level cultivators who make progress towards Immortality, often right when they enter a new cultivation stage. This typically takes the form of a lightning storm, with extraordinarily powerful bolts of lightning raining down from the Heavens to strike at the cultivator (source).

The trial by lightning is exactly like the calamity of thunder mentioned by Master Subodhi.

III. Conclusion

Subodhi teaches Monkey the 72 transformations with the expressed purpose of hiding from three calamities (sanzai lihai, 三災利害) of celestial lightening, fire, and wind. They are sent by heaven every 500 years to punish cultivators for defying their fate and achieving immortality. Each was likely influenced by the three calamities (sanzai, 三災) of Buddhist cosmology, which states that the universe is alternately destroyed by fire, water, or wind at the end of every Mahakalpa. Both concepts include destructive elemental forces that appear at given times.

The oldest mention of the original Buddhist calamities that I’m aware of appears in a 7th-century religious encyclopedia titled Pearl Forest of the Dharma Garden (Fayuan zhulin, 法苑珠林).

The literary thunder calamity would later come to influence the “Heavenly Tribulation” (tianjie, 天劫; zhongjie, 重劫) of modern Xianxia literature.

Update: 09-10-2018

The Xianxia translator Deathblade (twitter) was kind enough to direct me to an example of a tribulation from a popular Chinese television show . The scene (video 1) involves a 20,000-year-old child immortal experiencing a trial by lightning. The heavenly bolts tear at his clothing and draw blood, but he survives the ordeal.

Video 1 – Start watching from minute 13:08.

Deathblade also directed me to an example from an online Xianxia novel called I shall Seal the Heavens (Wo yu feng tian, 我欲封天). Chapter 385(!) describes how the anti-hero Meng Hao (孟浩) uses a sentient heavenly treasure to protect himself from powerful bolts of lightning, which instead seek out and kill nearby spiritual cultivators on the cusp of immortality:

The Heavenly Tribulation boomed as one lightning bolt after another shot down onto Meng Hao, who held the meat jelly upraised in his hand to defend himself. The lightning would subsequently disperse into the area around him. Any nearby Cultivators would let out bloodcurdling screams. Soon, the air filled with the sounds of cursing and reviling.

Meng Hao didn’t care. This was something he had learned from Patriarch Reliance. When you con someone and then end up getting cursed by them, you must maintain your cool. It was really a realm unto itself.

Throughout the years, Meng Hao had conned many people, and had refined that skill to the very pinnacle. Therefore, he continued to redirect the descending lightning to the various Cultivators in the three thousand kilometer region.

Wherever he went, he was surrounded by a lake of lightning, along with plaintive cursing. What he left behind was scorched corpses.

To the Cultivators here, it was nothing but a massacre, a slaughter in which no one could do anything to fight back. They couldn’t attack him, nor could they flee as… they were horrified to discover that Meng Hao’ speed was incredible, even if he was being struck by lightning!

The character uses trickery to protect himself from the bolts just like Monkey intended to do with his transformations.

Update: 04-02-2021

As I explained above, Wukong learns the 72 transformations in order to escape the heaven-sent punishments of thunder, fire, and wind. Monkey attains eternal life around his 342nd year when his soul is taken to Hell. He is immortal for over 160 years [2] at the time he’s imprisoned under Five Elements Mountain. This means his 500th year of immortality, the year that the calamity of thunder would be scheduled to strike him, takes place during his imprisonment under the celestial mountain. But this is never described in the story. I assume this is just one of many inconsistencies born from oral storytelling. Although, one could argue that, within the fictional universe, the thunder calamity was voided since Wukong was undergoing punishment at the behest of the Buddha.

Update: 03-25-22

My friend Irwen Wong of the Journey to the West Library blog was kind enough to give me a time-stamped link to the 1996 TV show containing the above episode. You’ll notice Sun Wukong is depicted as a young child. His reactions are hilarious.

Update: 08-29-22

It turns out that that punishment by lightning appears in other works of religious vernacular fiction. For example, in The Battle of Wits between Sun and Pang (Sun Pang douzhi yanyi, 孫龐鬥智演義, 1636; a.k.a. The Former and Latter Annals of the Seven Kingdoms, Qianhou qiguo zhi, 前後七國志):

Sun Bin [孫臏, d. 316 BCE] was overjoyed when he received the Heavenly Book [from the magic White Ape], and hurriedly went back to light the lamp and read it carefully. But during his reading, he felt an eerie, cold wind and heard the rolling of thunder. The Immortal Master Ghost Valley was meditating on the futon when he heard thunder in the air, so he got up and walked immediately to the door of Sun Bin’s room, only to see him reciting the Heavenly Book. When Ghost Valley heard this, he was taken aback. He pushed the door open and went in and said, “I hid this book in the stone box of the prayer cave. I haven’t passed it onto you because your fate has not yet arrived. Where did you get it?

Sun Bin told the story of the white ape. Ghost Valley said: “It turns out that the evil beast stole it and came to you, but unfortunately it was too early. Besides, when you received the Heavenly Book, you didn’t bathe and burn incense, and you didn’t wash your hands or rinse your mouth, thus blaspheming the gods and provoking a great tribulation [da zainan, 大災難] of 100 days.”

Sun Bin’s continence changed. He asked: “Can master save your disciple?”

Ghost Valley said: “If you want me to save you, you must not disobey my nightmare-suppression method.”

Sun Bin said: “I dare not.”

Ghost Valley said: “Due south behind the mountain is an empty stone tomb. You should sleep in the stone tomb with your head to the south and your feet to the north, with 49 grains of raw rice in your mouth. Cover it with your saliva but don’t swallow the grains. You will feel fully nourished. As long as you hide for forty-nine days, you will escape the great tribulation and protect yourself.”

Sun Bin said, “I sincerely receive your instructions.”

Ghost Valley led Sun Bin to the empty tomb at night. Sun complied with his master’s nightmare-suppression method and followed his instructions. A stele was erected in front of the tomb which read: “The Tomb of Sun Bin of the State of Yan” (Wumen xiaoke & Yanshui sanren, 1636).

Another example comes from the Lady of Linshui Pacifies Demons (Linshui pingyao, 臨水平妖, 17th-century). This time, it involves the immortal Lu Dongbin (呂洞賓; a.k.a. Lu Chunyang, 呂純陽) angering Guanyin, who dispatches thunder deities after him. And just like Sun learns the transformations to hide from the calamities, Lu takes the form of a bug to hide from his punishment:

As we take up our tale anew, Guanyin opened wide her eye of wisdom and saw Pure Yang Lü standing on top of the cloud. She cursed him, saying, “A dumb beast like that has no sense of propriety!” Then she sent the Five Thunders (Wu Lei [五雷]) to strike him. The Immortal Ancestor Lü saw them coming and for an instant was helpless with fright. Unable to escape back to his mountain, he hastily fled to Liang Hao’s study.

He called to Licentiate Liang, “In a moment of distraction, I offended the Heavenly Court, which has dispatched the Five Thunders to strike me. Save me!” As he spoke, the sound of thunder rolled violently. Liang Hao was so frightened that his hands and feet were like ice, and he was unable to reply. Pure Yang Lü said, “If you are willing to rescue me, then that would give this poor Daoist a place to hide.” Liang Hao agreed with alacrity. Pure Yang Lü then turned himself into a tiny insect, ran under Liang Hao’s fingernails, and hid himself. He waited for an hour and three quarters, until the thunder no longer rolled. There was nothing the Five Thunders could do, so they were obliged to go back to the Purple Bamboo Grove [on Guanyin’s mountain], having failed to carry out the Buddha’s [Guanyin’s] orders. At this time, an hour and three quarters having already elapsed, Pure Yang Lü resumed his original form. He thanked Liang Hao and returned to Zhong Mountain, as he did not dare remain in these harrowing circumstances any longer (Fryklund, Lewis, & Baptandier, 2021, p. 6).

Update: 11-09-22

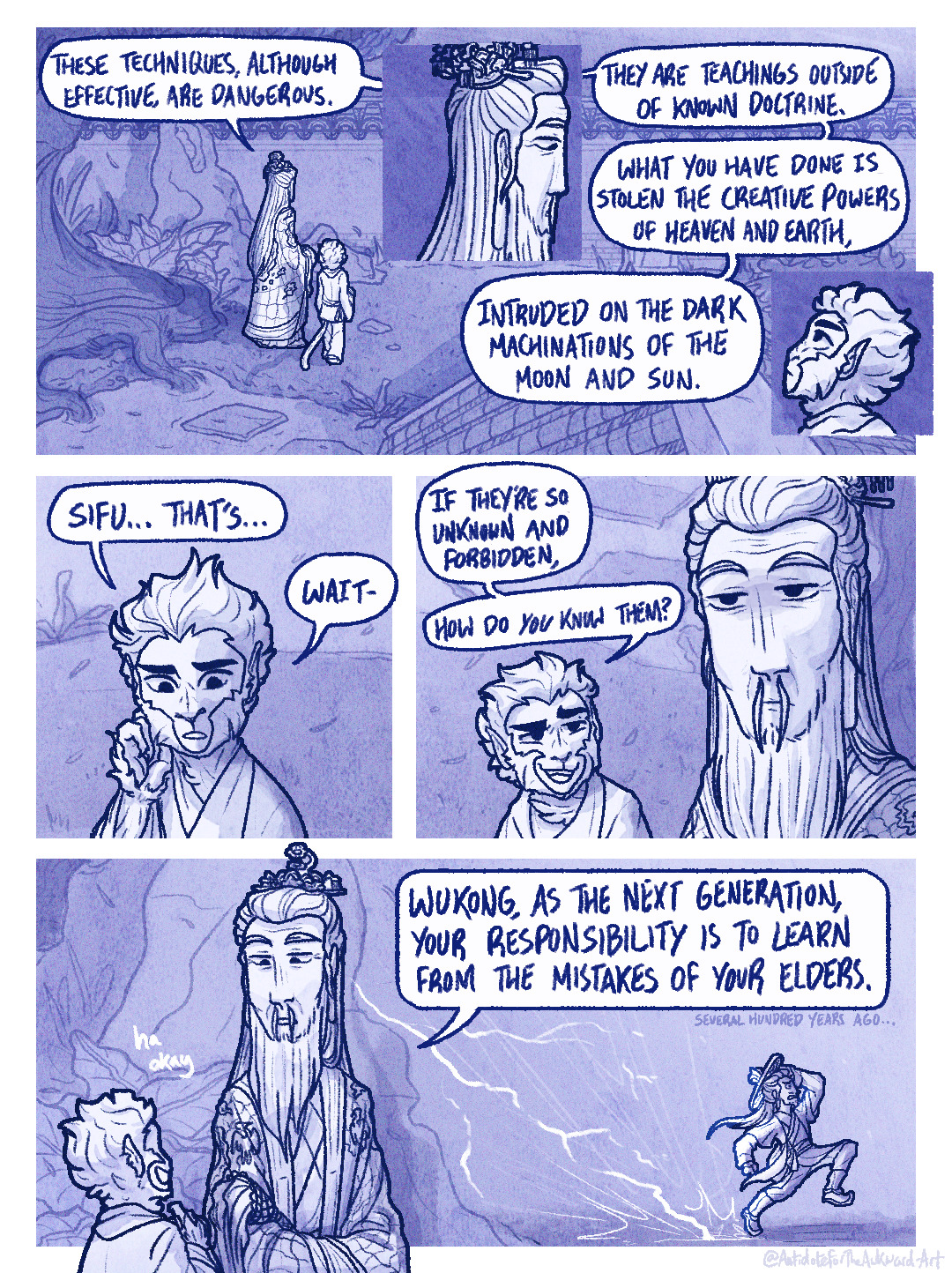

An artist known on Tumblr as “AntidoteForTheAwkward” has posted a wonderful comic (fig. 3) giving a reason for why the Patriarch Subhodi teachers Monkey the 72 transformations in order to avoid the heavenly calamities: personal experience.

Fig. 3 – AntidoteForTheAwkward’s comic (larger version). See the original post here.

Notes:

1) The eyes, ears, nose, mouth, genitals, and anus.

2) Wukong serves in heaven twice: first “for more than ten years” and second “for over a century” (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, pp. 150 and 166). Then he is punished to 49 days in Laozi’s furnace (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 189). But the narrative revels “one day in heaven is equal to one year on Earth” (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, pp. 150 and 167). So this means his turn in the furnace lasts close to fifty years.

Sources:

Buswell, J., & Lopez, D. (2014). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Fryklund, K. I., Lewis, M. E., & Baptandier, B. (2021). The Lady of Linshui Pacifies Demons: A Seventeenth-Century Novel. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

Kloetzli, R. (1983). Buddhist Cosmology: From Single World System to Pure Land: Science and Theology in the Images of Motion and Light. Oxford: Motilal Books.

Wu, C., & Yu, A. C. (2012). The Journey to the West (Vol. 1) (Rev. ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

Wumen xiaoke, & Yanshui sanren (1636). Qianhou qiguo zhi [Annals of the Seven Kingdoms]. Retrieved from https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=